Museum OOL

Some fathers build their daughters dollhouses. Ivan Honchak built his a model Lemko church.

Honchak, who was born in the Lemko village of Bortne in 1923 and taken to work in Germany in 1942, immigrated to the United States as a young man, but somehow managed to remember the minute details of the church in which he was christened.

As a little girl, Honchak's daughter liked to ask him questions about Lemkivshchyna – how had he lived, and what did he eat there? – so he decided to recreate, from memory, a detailed, smaller version of the Bortne church for her as something of a toy, he said.

“People ask me if I had a blueprint,” Honchak said. “No, God gave me the plans for it. God gave me the idea how to do it. I'm not an engineer. It just came to my head.”

That model of the 162-year-old, wooden Bortne church is now housed in the Lemko Museum in Stamford, CT for others to see. The Lemko Museum, which strives to preserve artifacts of Lemko regional culture, was recently renovated and can be viewed anytime by appointment.

Honchak was one of dozens of people who came to the Lemko Museum, located at St. Basil's Seminary, when it was open to the public for the Ukrainian Day Festival on September 12. He was happy to show the visitors his donated work, which also included wooden replications, complete with moving mechanical parts, of farm instruments used in Lemkivshchyna.

“Wow, you're talented,” said Andrea Boucher, 14, of Wyndham, CT to Honchak as she peered inside the model church. “It's beautiful. I'd be lucky if I remembered what I had last night for supper.”

Visitors filed past the exhibited Lemko pysanky , or Easter eggs, which are characteristic because of the short, quick strokes used to make them, and past reproduced works of Lemko artist Nikifor Drowniak, who, illiterate and disabled, acquired international renown in the 1960's for his water-colour paintings.

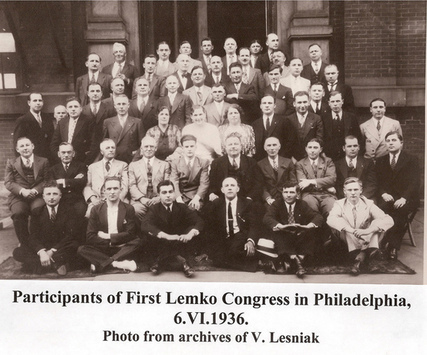

Other displays include Lemko folk costumes, wooden carvings, and pictures from historical Congresses of Lemko organizations.

Showing his young daughter around, Aleksander Zyla, 53, who was born in western Poland after his family was forcibly relocated from Lemkivshchyna in 1947, said he came to the museum to remember Lemko history and traditions.

“I always listened to my parents talking about the land they lived on. Kids in the U.S. don't understand unless you show them in reality,” said Zyla, who has been to the Lemko Museum approximately 10 times. “I love it. This is part of coming back here to the festival.”

Marta Rudyk of New Haven CT, a fifth-time visitor to the museum, said that she enjoys looking at the items donated by past generations, as well as having seen the museum grow little by little over the years.

The Lemko Museum, founded by the World Federation of Lemkos in the 1980's, was originally located in the home of Mr. Mykola Duplak in Syracuse, NY, before being moved to the two rooms it currently occupies at St. Basil's, said Steven Howansky, curator since 1993. The museum functions on the basis of volunteerism and donations.

Although there have not been many items added to the Lemko Museum recently, the existing artifacts have been displayed more clearly, with new descriptions that visitors can read, Howansky said.

“We want to preserve our tradition, our culture, our things that remained after our forefathers,” said Howansky, who was five-years-old when he was relocated with his family during Akcja “Wisla” in 1947. “We want our traditions to be kept because our history is interesting and close to our heart.”

Article written by Diana Howansky

For more information about the Ukrainian Lemko Museum, contact Lena Howansky at 203-703-8864.

Visits to the museum for both individuals and groups, particularly students, can be arranged.

Honchak, who was born in the Lemko village of Bortne in 1923 and taken to work in Germany in 1942, immigrated to the United States as a young man, but somehow managed to remember the minute details of the church in which he was christened.

As a little girl, Honchak's daughter liked to ask him questions about Lemkivshchyna – how had he lived, and what did he eat there? – so he decided to recreate, from memory, a detailed, smaller version of the Bortne church for her as something of a toy, he said.

“People ask me if I had a blueprint,” Honchak said. “No, God gave me the plans for it. God gave me the idea how to do it. I'm not an engineer. It just came to my head.”

That model of the 162-year-old, wooden Bortne church is now housed in the Lemko Museum in Stamford, CT for others to see. The Lemko Museum, which strives to preserve artifacts of Lemko regional culture, was recently renovated and can be viewed anytime by appointment.

Honchak was one of dozens of people who came to the Lemko Museum, located at St. Basil's Seminary, when it was open to the public for the Ukrainian Day Festival on September 12. He was happy to show the visitors his donated work, which also included wooden replications, complete with moving mechanical parts, of farm instruments used in Lemkivshchyna.

“Wow, you're talented,” said Andrea Boucher, 14, of Wyndham, CT to Honchak as she peered inside the model church. “It's beautiful. I'd be lucky if I remembered what I had last night for supper.”

Visitors filed past the exhibited Lemko pysanky , or Easter eggs, which are characteristic because of the short, quick strokes used to make them, and past reproduced works of Lemko artist Nikifor Drowniak, who, illiterate and disabled, acquired international renown in the 1960's for his water-colour paintings.

Other displays include Lemko folk costumes, wooden carvings, and pictures from historical Congresses of Lemko organizations.

Showing his young daughter around, Aleksander Zyla, 53, who was born in western Poland after his family was forcibly relocated from Lemkivshchyna in 1947, said he came to the museum to remember Lemko history and traditions.

“I always listened to my parents talking about the land they lived on. Kids in the U.S. don't understand unless you show them in reality,” said Zyla, who has been to the Lemko Museum approximately 10 times. “I love it. This is part of coming back here to the festival.”

Marta Rudyk of New Haven CT, a fifth-time visitor to the museum, said that she enjoys looking at the items donated by past generations, as well as having seen the museum grow little by little over the years.

The Lemko Museum, founded by the World Federation of Lemkos in the 1980's, was originally located in the home of Mr. Mykola Duplak in Syracuse, NY, before being moved to the two rooms it currently occupies at St. Basil's, said Steven Howansky, curator since 1993. The museum functions on the basis of volunteerism and donations.

Although there have not been many items added to the Lemko Museum recently, the existing artifacts have been displayed more clearly, with new descriptions that visitors can read, Howansky said.

“We want to preserve our tradition, our culture, our things that remained after our forefathers,” said Howansky, who was five-years-old when he was relocated with his family during Akcja “Wisla” in 1947. “We want our traditions to be kept because our history is interesting and close to our heart.”

Article written by Diana Howansky

For more information about the Ukrainian Lemko Museum, contact Lena Howansky at 203-703-8864.

Visits to the museum for both individuals and groups, particularly students, can be arranged.

Newly-renovated Ukrainian Lemko Museum Preserves Memories of Lemkivshchyna

Steven Howansky (right), curator of

Ukrainian Lemko Museum of Stamford, CT,

and Ivan Honchak (left)

stand in museum next to model Lemko church

made by Honchak. Picture courtesy of Bill Magac.

Ukrainian Lemko Museum of Stamford, CT,

and Ivan Honchak (left)

stand in museum next to model Lemko church

made by Honchak. Picture courtesy of Bill Magac.

Building a Lemko Museum beyond the Borders of Ukraine

For Lemko-Ukrainian immigrants to the United States, even the most difficult work was considered good fortune, and the lowest earnings offered the hope of survival. Memories of recent history flashed through their minds time and again – of wartime unrest, the horror of ruined churches converted into warehouses and barns, and the echoes of children’s sobs as Lemko families were thrown out of their houses. A longing for their native land prevented them from tossing away the key to their cozy home in the Carpathian Mountains.

For Lemko-Ukrainian immigrants to the United States, even the most difficult work was considered good fortune, and the lowest earnings offered the hope of survival. Memories of recent history flashed through their minds time and again – of wartime unrest, the horror of ruined churches converted into warehouses and barns, and the echoes of children’s sobs as Lemko families were thrown out of their houses. A longing for their native land prevented them from tossing away the key to their cozy home in the Carpathian Mountains.

Mr. Ivan Honchak was able to recreate for his children the Ukrainian ethnographic territory that he left behind, through a sort of enduring story. After work, in the little free time he had, Mr. Honchak constructed a model of his native home, a church on the hill, plowed fields, himself behind a plow, and fellow villagers. Much of the model showed people at work (because what was a Lemko without work), such as a girl sitting behind a spinning wheel, a young housewife making bread in the oven, and a man working outside. Mr. Honchak created everything with the greatest accuracy – the furnace for firing pottery, carpentry supplies, the spindle, and the distaff used for spinning wool. Everything was realistic, even the miniature loom for which Mr. Honchak weaved a piece of linen by hand.

Mr. Honchak’s children grew up, moved away, and created their own homes, but this model which remained from their childhood made its way, through some coaxing of Mr. Honchak’s friends, to a museum. It pleases the eye and warms the hearts of everyone who cares about the historical and cultural heritage of the Lemkos. The life and work of Mr. Honchak’s fellow countryman are most often depicted in this talented artisan’s creations, which can now be found in the Lemko Museum in Stamford, Connecticut.

It is good that such a Lemko Museum exists. It is just unfortunate that the Lemko Museum in Stamford is the only one in the United States. Even its establishment was not straightforward, however. The Lemko Museum was created through the painstaking efforts of expatriates such as Mr. Honchak Life in a foreign country, whether one likes it or not, leads to integration into the community in which one lives. But if Mr. Honchak’s generation could preserve their fleeting memories – of lively holidays, the interplay of colors and patterns united in embroidery, and the echoes of Ukrainians alpine horns among the tall Carpathian Mountains – then knowledge of their ancestors’ heritage could grow in their children’s hearts.

The colorfulness of American life led to a certain devaluation of the use of anything Ukrainian. Yet, it also encouraged the members of the organization named the Defense of Lemko-Western Ukraine (known by the acronym “OOL”) to think about establishing a museum. So that the “tree of Ukrainian heritage” would not wither when faced with other nations’ traditions and customs, the members of OOL felt they needed to do something. Everyone understood that they could only rely on their own efforts.

The organization dreamed about a space for the museum. But where would they get the money when many of the new Ukrainian immigrants did not even have a humane place to live? Thus, the first location was the home of OOL member Mr. Nicholas Duplak, where he fit everything that he and his colleagues managed to collect. Thanks to the sacrifices and work of Mr. Duplak, which he voluntarily took upon himself, a museum was created. He tirelessly collected, systematized, and restored, if necessary, everything that was a recollection and reflection of Ukraine and the Ukrainian life of Lemkos.

Over time, when the exhibits took over more space than a family’s small home could accommodate, the question of finding a special facility for the museum arose. Bishop Basil Losten provided the answer. A great patriot of everything Ukrainian, Bishop Losten provided two rooms in the Diocesan House in Stamford for the Lemko collection. One advantage of this facility was the fact that a Ukrainian Museum was already functioning there.

Established in 1933, the Ukrainian Museum was the first of its kind in North America, and still stands out among similar institutions today, not only because of the diversity and richness of its exhibits, but also because of its extensive library with more than 20 thousand volumes of books. Housed in this library are the complete works of Taras Shevchenko, the writings of Ivan Franko, other classics, and publications by modern authors. Not without reason does the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute even readily make use of the library’s resources.

Rumors about the newly established Lemko Museum spread quickly among the Lemko community, like an echo in the mountains. People donated more and more gifts. Now, the two rooms, which seemed large and spacious at first, have again become tightly packed with numerous exhibits, thanks in part to the current curator of the museum’s treasures, Mr. Steven Howansky. The museum houses all kinds of crafts and folk arts that were common in Ukrainian ethnographic territories, some in their original form and some that are miniature copies. There are only two rooms, but one can spend the entire day looking at the museum items – crafts carved out of wood, collections of combs and spoons, embroidered shirts and towels, Lemko ethnic clothing, ceramics, reproductions of the Lemko artist Nikifor’s artwork, etc. – without getting bored and losing track of time.

Mr. Howansky laments that space is sorely lacking. The museum has preserved a huge literary archive, predominantly about the history of the Lemko region, research about wooden architecture of the Ukrainian Carpathian Mountains, a complete collection of the “Annals of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army” (UPA), a variety of photographs and documents – all attesting to actual events that took place in real life. Still, the Lemko Museum could use a couple of mannequins on which to hang the clothes it stores and several showcases in which to exhibit the unique collection of Ukrainian Easter eggs that were donated by a Lemko couple in Canada.

There is no staff at the Lemko Museum. Mr. Howansky assumed the responsibility for taking care of the museum and, often with help from his family, makes repairs, cleans, and catalogues items. Other volunteers like Mr. Howansky also come together to help. Their communal work is a model for others. These people have united to build the dream of Ukraine outside of Ukraine, in order to convey information about Ukrainian culture, language, and traditions to Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians alike, to show the unity of Ukrainians through time and space, and to better understand themselves and their place in this world.

For Lemko-Ukrainian immigrants to the United States, even the most difficult work was considered good fortune, and the lowest earnings offered the hope of survival. Memories of recent history flashed through their minds time and again – of wartime unrest, the horror of ruined churches converted into warehouses and barns, and the echoes of children’s sobs as Lemko families were thrown out of their houses. A longing for their native land prevented them from tossing away the key to their cozy home in the Carpathian Mountains.

For Lemko-Ukrainian immigrants to the United States, even the most difficult work was considered good fortune, and the lowest earnings offered the hope of survival. Memories of recent history flashed through their minds time and again – of wartime unrest, the horror of ruined churches converted into warehouses and barns, and the echoes of children’s sobs as Lemko families were thrown out of their houses. A longing for their native land prevented them from tossing away the key to their cozy home in the Carpathian Mountains. Mr. Ivan Honchak was able to recreate for his children the Ukrainian ethnographic territory that he left behind, through a sort of enduring story. After work, in the little free time he had, Mr. Honchak constructed a model of his native home, a church on the hill, plowed fields, himself behind a plow, and fellow villagers. Much of the model showed people at work (because what was a Lemko without work), such as a girl sitting behind a spinning wheel, a young housewife making bread in the oven, and a man working outside. Mr. Honchak created everything with the greatest accuracy – the furnace for firing pottery, carpentry supplies, the spindle, and the distaff used for spinning wool. Everything was realistic, even the miniature loom for which Mr. Honchak weaved a piece of linen by hand.

Mr. Honchak’s children grew up, moved away, and created their own homes, but this model which remained from their childhood made its way, through some coaxing of Mr. Honchak’s friends, to a museum. It pleases the eye and warms the hearts of everyone who cares about the historical and cultural heritage of the Lemkos. The life and work of Mr. Honchak’s fellow countryman are most often depicted in this talented artisan’s creations, which can now be found in the Lemko Museum in Stamford, Connecticut.

It is good that such a Lemko Museum exists. It is just unfortunate that the Lemko Museum in Stamford is the only one in the United States. Even its establishment was not straightforward, however. The Lemko Museum was created through the painstaking efforts of expatriates such as Mr. Honchak Life in a foreign country, whether one likes it or not, leads to integration into the community in which one lives. But if Mr. Honchak’s generation could preserve their fleeting memories – of lively holidays, the interplay of colors and patterns united in embroidery, and the echoes of Ukrainians alpine horns among the tall Carpathian Mountains – then knowledge of their ancestors’ heritage could grow in their children’s hearts.

The colorfulness of American life led to a certain devaluation of the use of anything Ukrainian. Yet, it also encouraged the members of the organization named the Defense of Lemko-Western Ukraine (known by the acronym “OOL”) to think about establishing a museum. So that the “tree of Ukrainian heritage” would not wither when faced with other nations’ traditions and customs, the members of OOL felt they needed to do something. Everyone understood that they could only rely on their own efforts.

The organization dreamed about a space for the museum. But where would they get the money when many of the new Ukrainian immigrants did not even have a humane place to live? Thus, the first location was the home of OOL member Mr. Nicholas Duplak, where he fit everything that he and his colleagues managed to collect. Thanks to the sacrifices and work of Mr. Duplak, which he voluntarily took upon himself, a museum was created. He tirelessly collected, systematized, and restored, if necessary, everything that was a recollection and reflection of Ukraine and the Ukrainian life of Lemkos.

Over time, when the exhibits took over more space than a family’s small home could accommodate, the question of finding a special facility for the museum arose. Bishop Basil Losten provided the answer. A great patriot of everything Ukrainian, Bishop Losten provided two rooms in the Diocesan House in Stamford for the Lemko collection. One advantage of this facility was the fact that a Ukrainian Museum was already functioning there.

Established in 1933, the Ukrainian Museum was the first of its kind in North America, and still stands out among similar institutions today, not only because of the diversity and richness of its exhibits, but also because of its extensive library with more than 20 thousand volumes of books. Housed in this library are the complete works of Taras Shevchenko, the writings of Ivan Franko, other classics, and publications by modern authors. Not without reason does the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute even readily make use of the library’s resources.

Rumors about the newly established Lemko Museum spread quickly among the Lemko community, like an echo in the mountains. People donated more and more gifts. Now, the two rooms, which seemed large and spacious at first, have again become tightly packed with numerous exhibits, thanks in part to the current curator of the museum’s treasures, Mr. Steven Howansky. The museum houses all kinds of crafts and folk arts that were common in Ukrainian ethnographic territories, some in their original form and some that are miniature copies. There are only two rooms, but one can spend the entire day looking at the museum items – crafts carved out of wood, collections of combs and spoons, embroidered shirts and towels, Lemko ethnic clothing, ceramics, reproductions of the Lemko artist Nikifor’s artwork, etc. – without getting bored and losing track of time.

Mr. Howansky laments that space is sorely lacking. The museum has preserved a huge literary archive, predominantly about the history of the Lemko region, research about wooden architecture of the Ukrainian Carpathian Mountains, a complete collection of the “Annals of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army” (UPA), a variety of photographs and documents – all attesting to actual events that took place in real life. Still, the Lemko Museum could use a couple of mannequins on which to hang the clothes it stores and several showcases in which to exhibit the unique collection of Ukrainian Easter eggs that were donated by a Lemko couple in Canada.

There is no staff at the Lemko Museum. Mr. Howansky assumed the responsibility for taking care of the museum and, often with help from his family, makes repairs, cleans, and catalogues items. Other volunteers like Mr. Howansky also come together to help. Their communal work is a model for others. These people have united to build the dream of Ukraine outside of Ukraine, in order to convey information about Ukrainian culture, language, and traditions to Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians alike, to show the unity of Ukrainians through time and space, and to better understand themselves and their place in this world.

Written in original Ukrainian by Nadia Burmaka Translated into English by Diana H. Reilly